“The way we’ve been managing marine resources [is] going to be especially inadequate in a changing climate... The stakes are so much higher…having the right tools…is more important now than ever. I think a threshold-based approach could be an incredibly valuable asset to help insure that we are able to improve our management of reefs not just for today but with the idea in mind of resilience for tomorrow.”

Coral reef management in Hawai'i - Using tipping points science to maintain resilient coral reefs

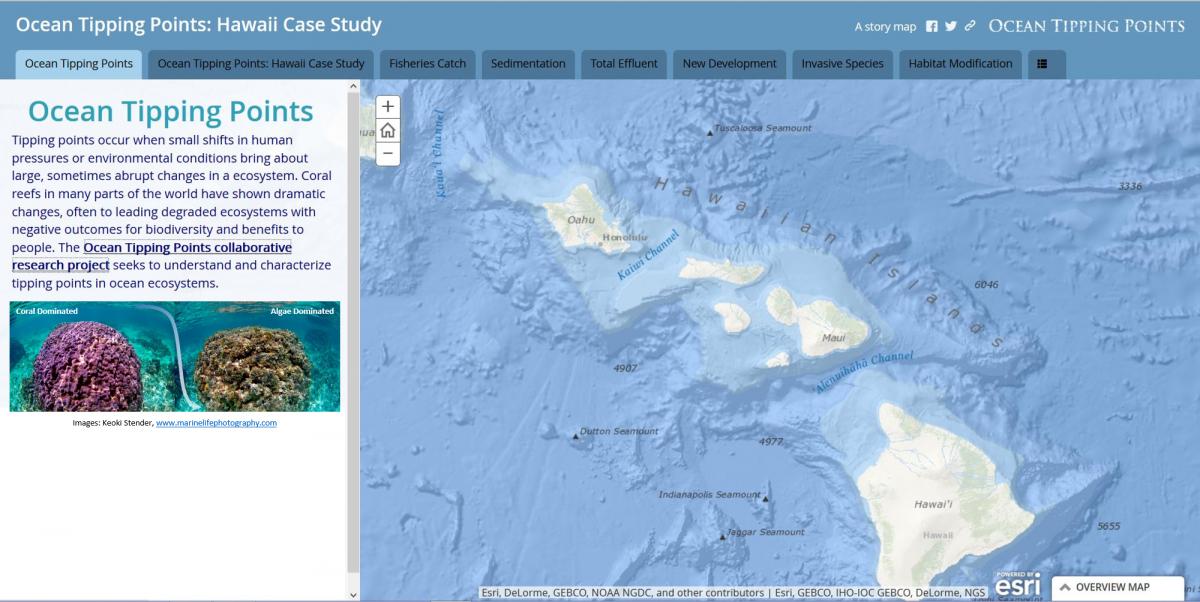

Through an in depth study of the reefs of Hawaii, our team explored the natural and human drivers of ecosystem change on coral reefs, leading to new insights and decision support tools to maintain healthy, resilient reefs in Hawaii and around the world.

Key take-aways from our research:

follow links to a section of interest or read on for the full story

- Overfishing, nutrient input, sedimate and climate change have caused dramatic declines in reef health worldwide.

- Understanding causes and warning signs of reef tipping points can help prioritize management actions and monitoring strategies, and inform conservation and restoration targets.

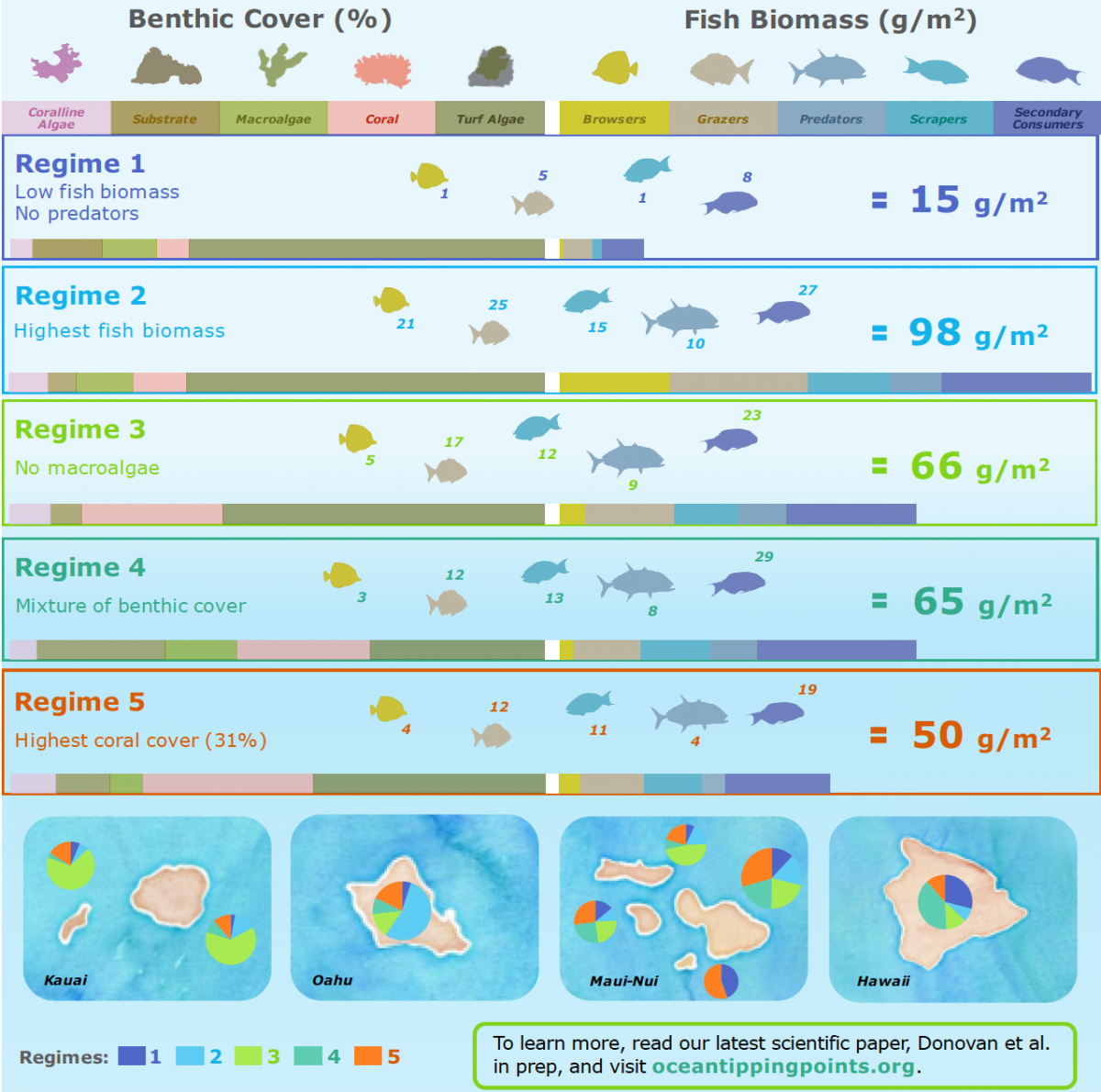

- The view that coral reefs are either healthy and coral-dominated, or unhealthy and algal-dominated, is overly simplistic for Hawaiian reefs

- Coral reefs can exist in multiple different ecosystem states

- New techniques allow us to disentangle the environmental and human drivers associated with these different states

- Quantifying the threshold levels of drivers that lead to reef shifts can help to inform appropriate management targets

- Tradeoff analysis highlights cost-effective management options and the value of cooperation among land-owners in addressing land based source pollution to protect nearshore reefs

Background

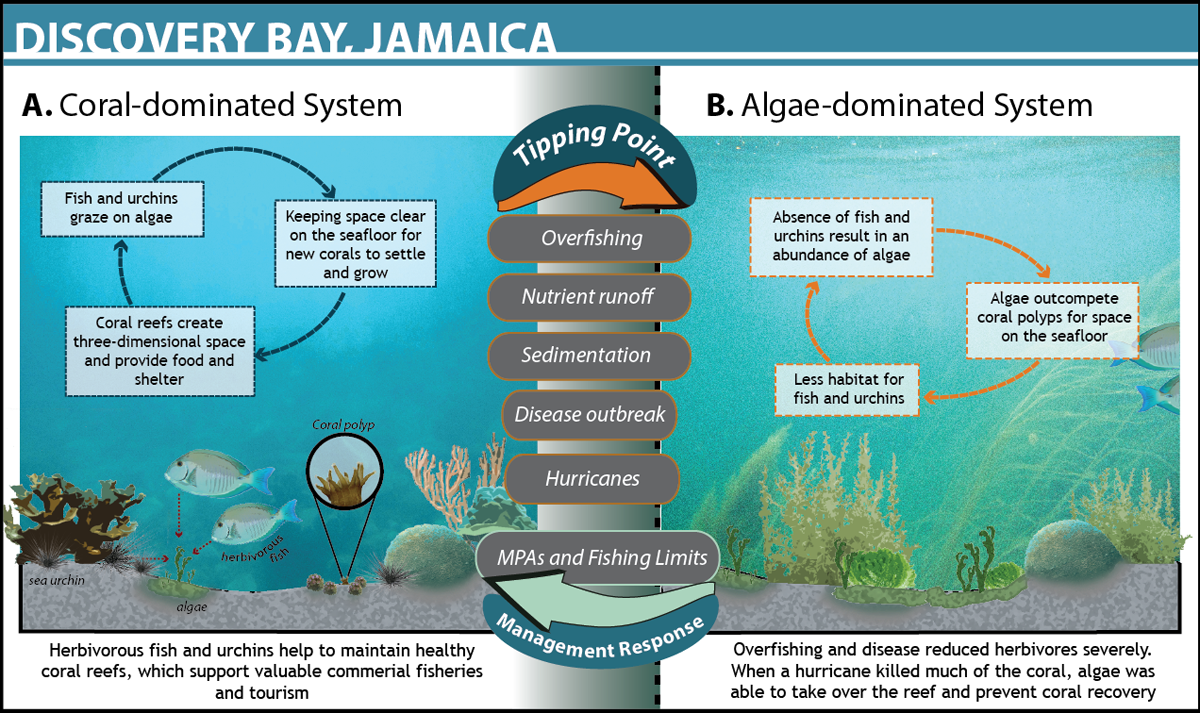

Researchers started to suspect tipping points in coral reef communities decades ago, beginning with the shifts from vibrant, diverse coral reefs to degraded reefs overrun with algae, observed in the Caribbean in the 1980s and 1990s. Long-term overfishing, especially of herbivorous fishes, and nutrient runoff eroded the resilience of coral-dominated ecosystems to recover from hurricanes and disease, and promoted the dominance of fleshy algae. By the turn of the century, it was clear that many Caribbean reefs had crossed a tipping point, and re-establishing healthy coral communities would be difficult, if not impossible, in our lifetimes.

The changes observed on Caribbean reefs in the 1980s proved to be the “canary in the coal mine,” with reefs across the world experiencing similar dramatic shifts as a result of rising local and global stressors, including land-based pollution, overfishing, and climate change. The number and variety of stressors that interact across the land-sea interface and across scales to affect reefs highlight the need for coordination across multiple agencies with different mandates, authorities and jurisdictions. Increasingly, communities and decisionmakers recognize the need to mitigate local stressors to enhance reef resilience in the face of global climate change. At risk is a suite of valuable benefits that coral reefs provide to coastal communities. Loss of coastal protection, fishing, tourism opportunities, and other benefits impact local economies, jobs and culture.

Limited resources and time and a daunting array of both problems and potential management solutions result in a triage situation. Understanding the causes and warning signs of tipping points in coral reefs can help prioritize effective management actions and monitoring strategies and inform appropriate conservation and restoration targets1,2. Applying a tipping point approach is necessary but not sufficient: good governance is also critical3.

In the US, aspects of coral reef management fall under both state and federal management (as prescribed by the Magnuson Stevens Act, Clean Water Act, Coastal Zone Management Act, National Environmental Protection Act, Sanctuaries Act, Endangered Species Act, Coral Reef Conservation Act, and US Ocean Policy). In most if not all of these laws, there is scope for the application of ecological thresholds as reference points for reef health and for the use of scientifically informed strategies to address key land- and ocean-based drivers and build reef resilience.

We took a deep dive into tipping point science to see how it might enhance coral reef management in our Hawaii case study.

Hawaiian reefs – a case study

Like reefs elsewhere around the world, the condition of many Hawaiian reefs has declined due to interacting land- and ocean-based threats. However Hawaii sits in colder, rougher waters than most coral reefs, and its reefs are naturally more variable in coral cover, algal cover and overall reef community structure. Therefore, Hawaiian reefs may not conform to the simple view that reefs are either coral-dominated and ‘healthy’ or algal-dominated and ‘degraded’; a more nuanced view of reef tipping points may be necessary.

Leveraging one of the most extensive reef monitoring datasets ever compiled and new comprehensive maps of human and environmental drivers of reef change, our collaborative team built a novel view of Hawaiian nearshore reefs and the factors that interact to shape them. With this information, we are developing a suite of tools and analyses to support management in the face of reef change:

- Characterization of reef regimes with quantitative metrics that distinguish human-caused degradation from natural variation

- Leading indicators that can provide early warning that a reef may be approaching an ecosystem tipping point,

- Prioritization of places and stressors most in need of management action

- Quantified thresholds that serve as reference points to help managers understand how much stress may push a reef past a tipping point, and

- Tradeoff analysis to weigh the costs and benefits of different management options, with a first analysis focused on watershed management in West Maui.

This integrated analysis of the state of Hawaii’s reefs, co-developed with our management partners, can enhance restoration and reduce the chance of surprising, costly, and potentially irreversible changes to the ecosystem and the people who depend upon it. Our outputs are tools, maps, and guiding principles to help practitioners effectively anticipate, avoid, and respond to coral reef change in Hawai‘i and beyond.

Compiling reef monitoring data across the Main Hawaiian Islands

Hawaii has few continuous long-term monitoring datasets, but has been extensively studied through one-time or short-term efforts. Faced with the paucity of time series data, we focused on a “space-for-time substitution” approach, drawing on data from the nearly 6000 sites that had been surveyed at least once since 2000. This allowed us to look at spatial patterns in reef community composition, environmental factors and human activities and develop hypotheses about reef change through time and then use our more limited temporal data to explore those hypotheses.

Expanding upon previous efforts, we compiled the most comprehensive database of fish and reef data available for the Hawaiian Islands. To make the data comparable, we carefully calibrated across methods to combine information from numerous monitoring programs4.

Characterizing reef regimes

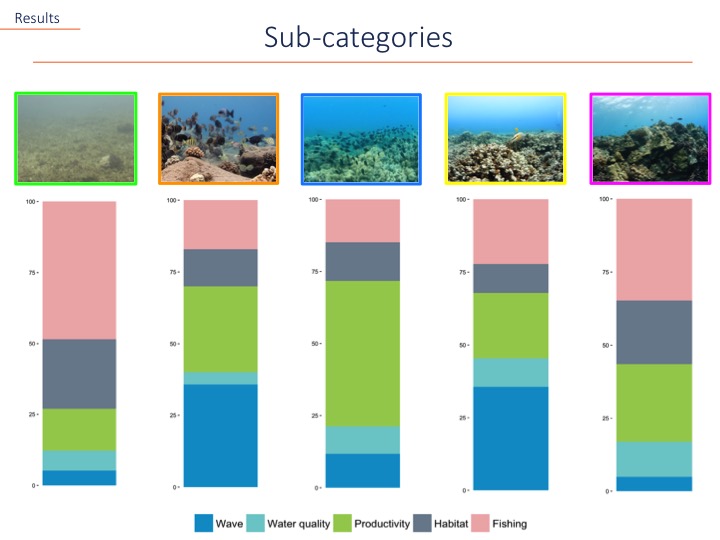

To better understand the diversity of reef types and potential reef changes in Hawaii, we used both benthic and fish data to define reef regimes5. Previous efforts have relied solely on benthic cover (i.e. coral versus algae) to define reef state. Our more holistic, ecosystem based approach to identifying reef regimes is novel for treating the fish community as a component of the ecosystem instead of a driver of the ecosystem. Our analysis provides a more nuanced understanding of reef regimes, revealing five distinct reef types, in contrast to the traditional perception of only two dominant states:

Mapping these regimes enhances our understanding of the distribution and variation of reefs across Hawai‘i.

Complementary time series data allowed us to look at transitions among reef regimes explicitly for 65 sites. This analysis showed that while all possible regime transitions are possible, some are more likely (e.g., 4->1, 4->5) and some regimes appear more stable through time, (e.g., regimes 1 and 2). The variety of transitions observed suggests that reef change is a more subtle and variable process than implied by the simple view that under stress reefs degrade from “healthy,” coral-dominated to “unhealthy,” algal-dominated. Exploring the distinctions that separate regimes, and patterns of transitions among them, helps establish a baseline for measuring reef change and prioritizing protection for reefs prone to tipping points.

To learn more, click here.

Mapping environmental and human drivers of reef regimes

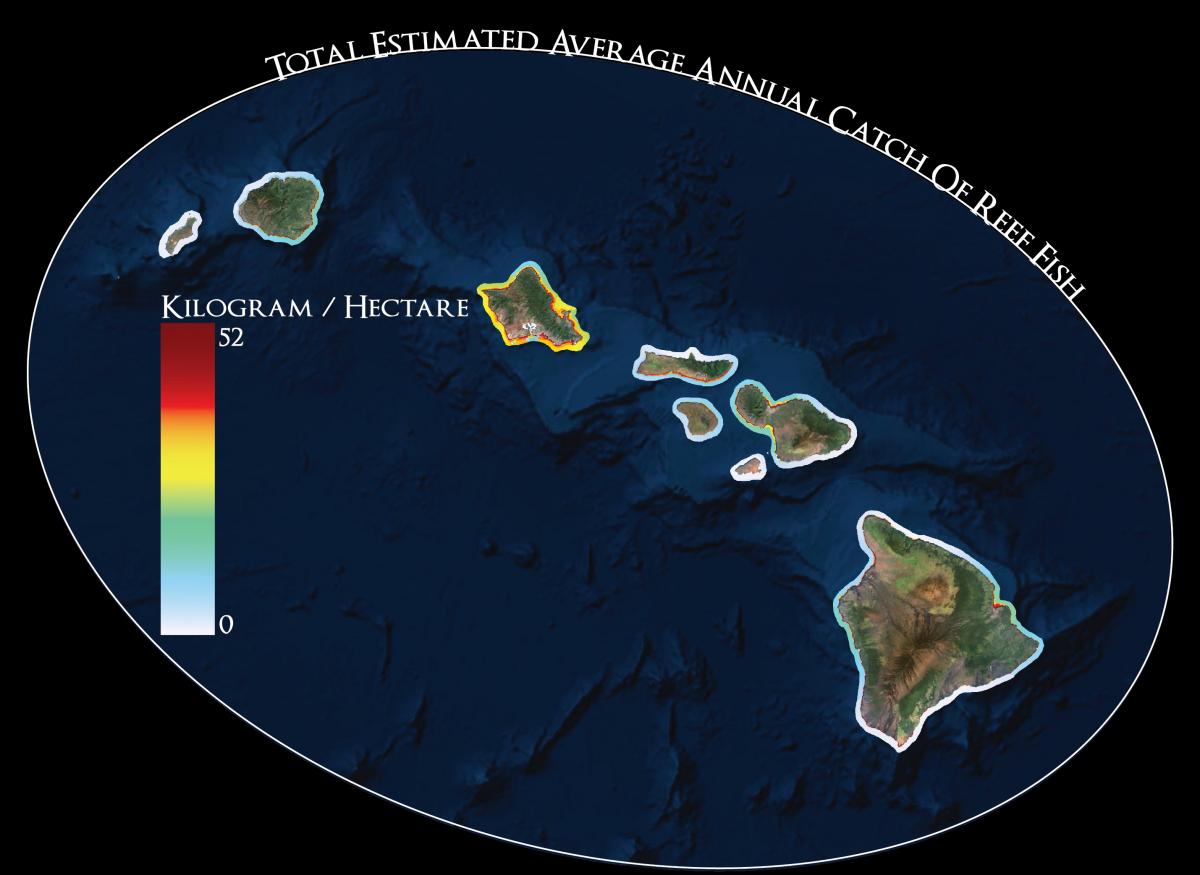

We created statewide maps showing the distribution and intensity of human and environmental drivers of coral reef ecosystem state across Hawai‘i6. The environmental driver data were gathered from recent satellite-based sea surface temperature, chlorophyll-a, irradiance, and modeled wave energy data. Human drivers of coral reef ecosystem health included data on commercial and non-commercial fish catch, invasive species, effluent, habitat modification, and sedimentation on reefs.

Example data layer representing reef fish catch across Hawaii. For more details and to download datasets go to PacIOOS.

Not surprisingly, levels of many human impacts are highest on Oahu, including habitat modification, invasive species, and boat-based fishing pressure. Sedimentation and nutrient runoff are the dominant influences in specific locations on Maui, the Big Island, and North Shore of Oahu. The analysis of environmental drivers showed strong variation in productivity and mixing across the archipelago related to coastline shape and orientation.

With an integrated and comprehensive picture of how both human and environmental drivers of coral reef health vary in space across the Hawaiian Archipelago, managers can start to prioritize places and management actions. You can explore the maps interactively in our storymap, and the datasets are publically available on PacIOOS for download.

To learn more, click here.

Linking regimes to environmental and human drivers and quantifying thresholds

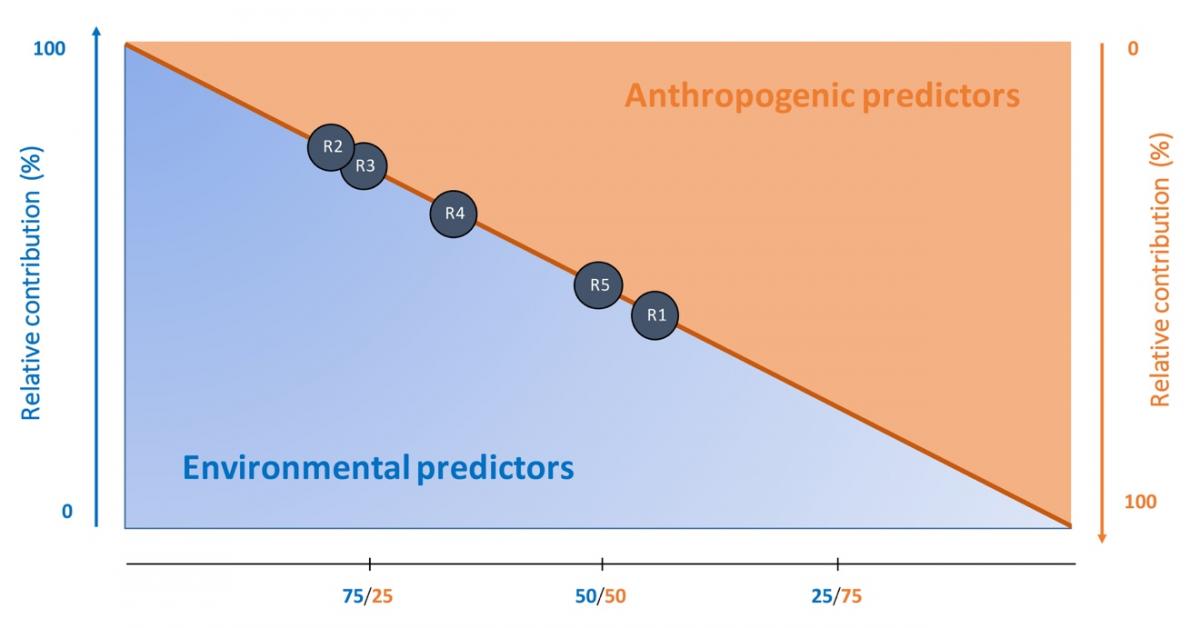

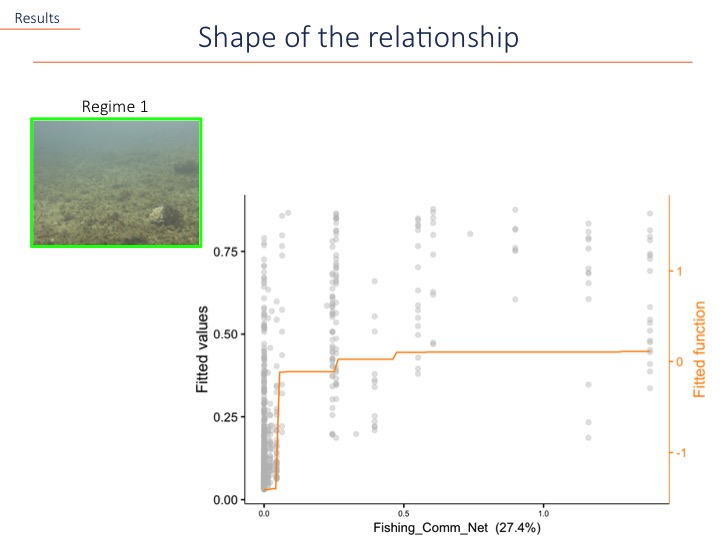

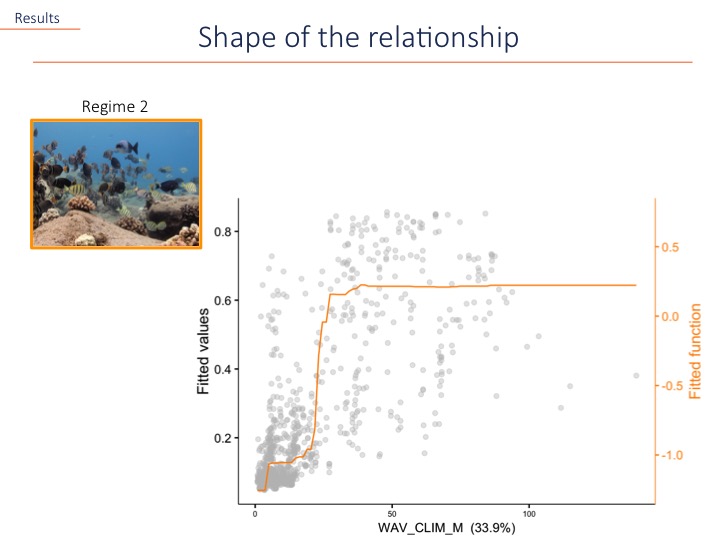

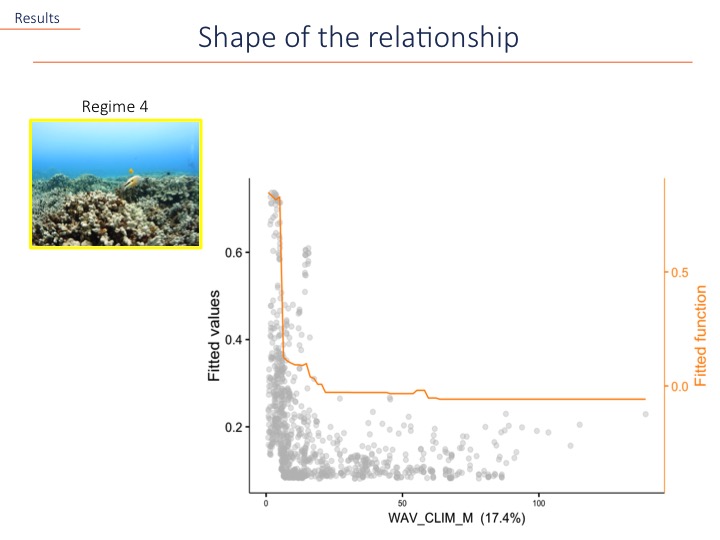

Next we used a statistical modeling approach to understand which drivers are most important in explaining the distribution of a given reef regime and the relative influence of environmental versus human factors7. The technique is a machine learning approach called Boosted Regression Trees (BRT). This technique relates the presence/absence of each reef regime to individual drivers and their interactive effects.

The analysis also produces scatter plots that reveal the shape of the relationship between each regime and each driver. Threshold relationships between drivers and regimes can be quantified with these plots.

Evaluating management alternatives using tradeoff analysis

Increased runoff of sediment and pollutants from land threaten coral reef ecosystems around the world. These land-based source pollutants (LBSP) have been linked to degradation on some Hawaiian reefs. As an example of how to quantitatively evaluate management options for reducing key drivers of reef change, we developed a decision support tool that analyzes the costs and benefits of different management strategies aimed at reducing LBSP8. Specifically, we examined the tradeoffs, in terms of management cost and sediment reduction, among potential agricultural road repair management actions in West Maui, Hawai‘i. We identified the most cost-effective roads to repair (the most sediment reduction per dollar spent), and found significant cost savings when landowners repaired these. We further discovered the best environmental gains for lowest economic cost could be achieved when landowners cooperated, although the benefits of cooperation dissipate if landowners do not target cost-effective roads. These decision tools can help managers make better environmental decisions with limited resources. We plan to undertake additional tradeoff analyses to examine other drivers of nearshore water quality and reef change in the future.

Informing priorities for spatial, ecosystem based management

Improving the health and resilience of Hawaii’s reefs is a priority of local community groups and state and federal agencies. For the first time, in 2015-2016 the state experienced extensive coral bleaching, sounding the alarm that more needs to be done to protect this fragile habitat. Numerous efforts have been spurred by this wakeup call and by projections that suggest that bleaching may become an annual event by the middle of this century9. These include the creation of a Coral Bleaching Response Task Force charged with making management recommendations, new proposals for community-based marine managed areas, and the ‘Hawai‘i 30 by 30 Oceans Target.’ This state initiative aims to have 30% of Hawaii’s nearshore waters under effective management by 2030.

Our team is working closely with partners on the ground to ensure that the results of our science help to inform these efforts, shedding light on key drivers, priority areas for protection, and the costs and benefits of different management options. This is a work in progress, and we invite you to stay connected to learn alongside us.

Learn more

Explore the Hawaii case study through this interactive storymap:

Download many of the datasets developed through this case study at PacIOOS

References

-

Donovan et al. in prep (fish meta-analysis)

-

Donovan et al. in prep (regimes paper)

-

Wedding et al. in prep

-

Jouffray et al. in prep