Ecosystem indicators

Indicators are measurements of the social-ecological system that reveal its condition, composition, structure, function, and processes. Managers use suites of indicators to detect changes in ecosystem status and trends, to evaluate current and past policy decisions, and to help plan for the future. For ecosystems that exhibit threshold dynamics, indicators that provide early warning of change (i.e., early warning or leading indicators) can help managers avoid crossing tipping points or monitor progress of restoration efforts in systems that have already crossed tipping points. For example, measures of variance in components in ecosystem that respond more rapidly to change may provide earlier warning of impending transitions. One example from Pacific ecosystems is the rise in spatial variance in crustacean fisheries catches in Alaska prior to fisheries collapses.21 Social drivers (e.g., education, ownership, an settlement patterns) often precede ecological drivers by years or decades and may also serve as early warning of ecosystem shifts.22

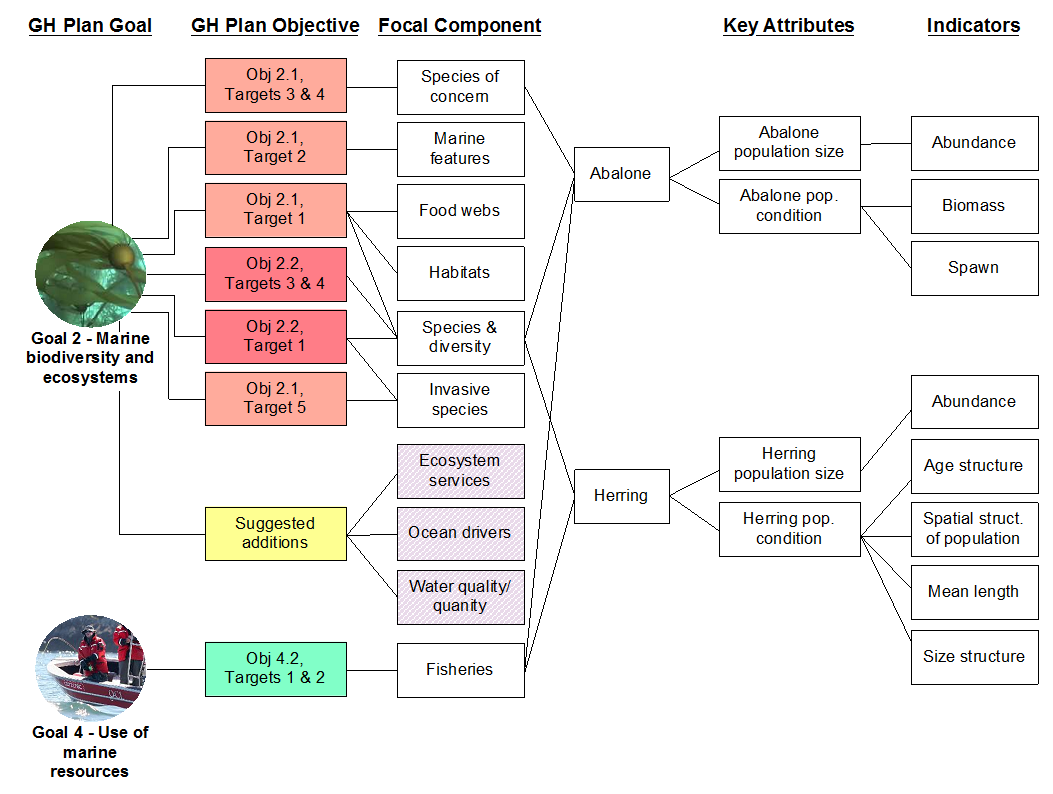

Given limited resources, the goal is to identify a set of indicators that can provide adequate information on status and trends and determine whether reference points or targets have been met and management goals achieved. In the face of tipping points, managers may want to include a number of early warning indicators in their portfolio. For example, in Haida Gwaii, Pacific herring are key components in a broader ecosystem and would be a strong candidate indicator to track overall ecosystem status. To manage ecosystems in Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area and Haida Heritage Site, managers needed to identify key components and determine indicators to include in their management and monitoring plans. To help inform their selection of a portfolio of indicators, the Ocean Tipping Points team identified a suite of potential indicators using a framework from NOAA's Integrated Ecosystem Assessment developed for the California Current Large Marine Ecosystem.

Applying this hierarchical framework we developed conceptual models of linked ecosystem components and drivers of change for a range of ecosystems and then used a semi-quantitative, expert elicitation approach to compare sets of potential indicators for each ecosystem type across a range of sensitivity and specificity axes, with an emphasis on identifying leading indicators. Conceptual models provided managers an opportunity to identify linkages and key gaps in indicator portfolios for a range of ecosystems, including herring-centric pelagic ecosystems. Furthermore, for Gwaii Haanas and other managed areas, management constraints influence how indicators are chosen. For example, many systems already have ongoing monitoring in place, affecting the bottom line of what can be added. We compared indicator portfolios from the hierarchical framework to those identified from ongoing monitoring programs with cost constraints. This helped managers to emphasize those indicators they should maintain and identified potential indicators that would help fill gaps in their monitoring plan. For systems that experience tipping points, applying portfolio assessments can help managers assess the value of added information and help fill gaps in monitoring plans with indicators that can help identify impending shifts.