Sociocultural values and sustainability

Coupled social-ecological systems are made up of many social groups often with competing needs for, relations to, and values of the environment and natural resources. In many cases, despite these differing needs and values, people’s well-being is coupled in one or more ways to the health of ecosystems. Thus, managing natural resources requires consideration of multiple stakeholders’ values and preferences. Understanding social-ecological linkages, detecting sociocultural thresholds and eliciting people’s preferences for particular ecosystem states can help managers define management targets for recovery and understand potential trade-offs that might arise with different decisions.

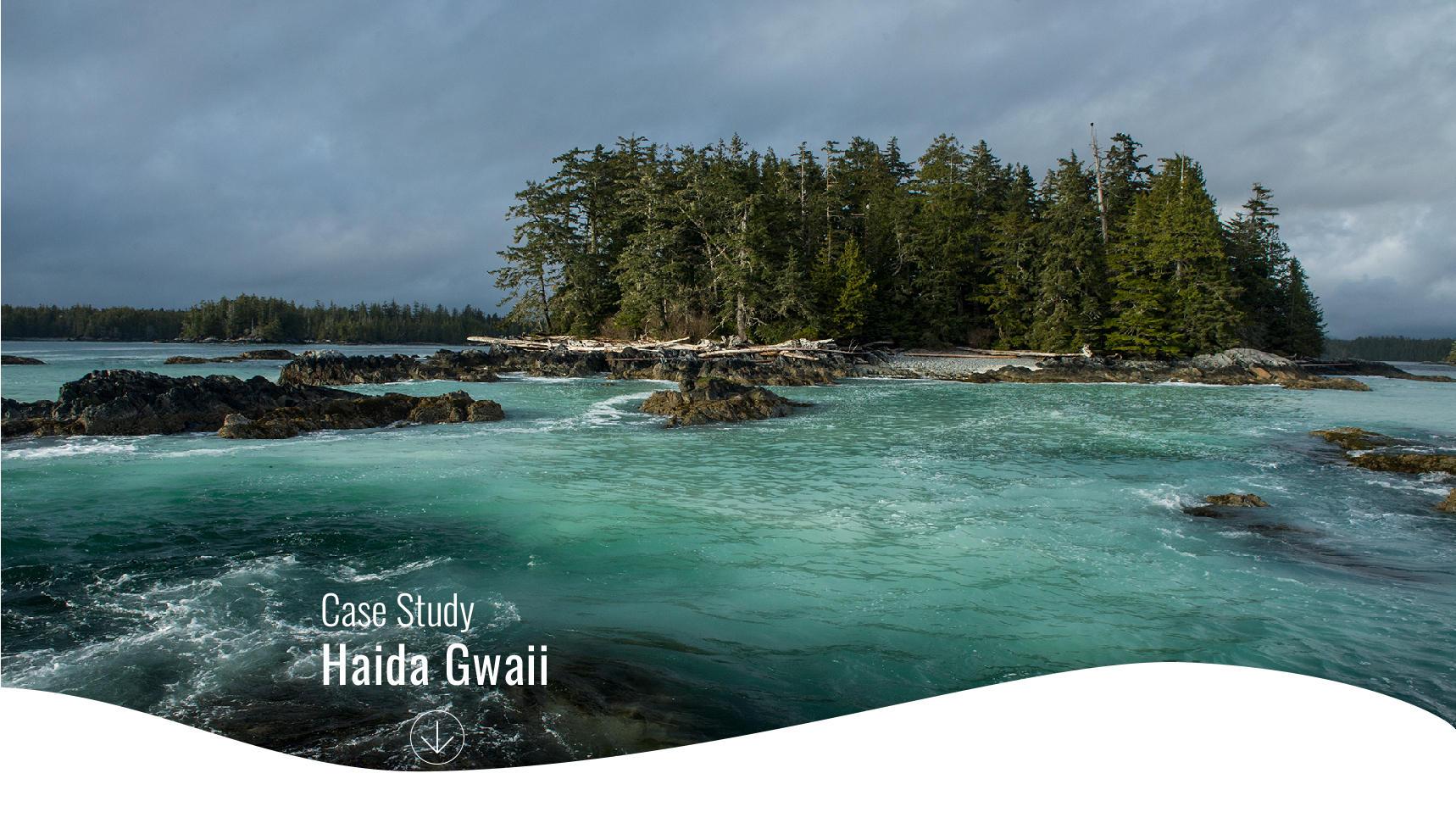

Characterizing sociocultural values related to herring to inform social-ecological thresholds

Pacific herring are key species that contribute to cultural, social and economic well-being in Haida Gwaii. Herring have been central to Haida lives, livelihoods and culture for thousands of years15,16,17,18. To understand the diverse sociocultural values and practices regarding herring, we worked with the Haida Nation and a cultural liaison to conduct open-ended interviews with Haida community members and knowledge holders (n=39). The men and women who participated in interviews included traditional food harvesters, commercial herring and roe on kelp fishermen, cultural teachers, resource managers and local leaders from both Masset and Skidegate villages. Extended interviews helped us characterize the range of social impacts of ecological and management changes, both past and future, and is helping guide goal-setting for fisheries and ecosystem managers in Haida Gwaii. Linking Haida values for and relationships with herring with the spatio-temporal changes in herring populations, we identified potential social-ecological tipping points in the system. Specifically, we identified thresholds of herring abundance and distribution that exist for meeting cultural objectives. Such cultural objectives include, for example, resource access, knowledge sharing, identity, cultural food and feasting practices, conservation ethics, spiritual importance, and community social relationships. When there is enough herring and roe on kelp to harvest in the right places at the right time, community members can take part in harvesting and share knowledge across generations about where and how to harvest, process and use herring, and maintain these cultural values. Herring roe on kelp, known locally as k'aaw, is an important food in the seasonal round and contributes to community well-being, health and food sharing. In addition to these harvest values, herring are important to Haida as a way to connect with the ocean and other animals linked to herring.

Pacific herring are key species that contribute to cultural, social and economic well-being in Haida Gwaii. Herring have been central to Haida lives, livelihoods and culture for thousands of years15,16,17,18. To understand the diverse sociocultural values and practices regarding herring, we worked with the Haida Nation and a cultural liaison to conduct open-ended interviews with Haida community members and knowledge holders (n=39). The men and women who participated in interviews included traditional food harvesters, commercial herring and roe on kelp fishermen, cultural teachers, resource managers and local leaders from both Masset and Skidegate villages. Extended interviews helped us characterize the range of social impacts of ecological and management changes, both past and future, and is helping guide goal-setting for fisheries and ecosystem managers in Haida Gwaii. Linking Haida values for and relationships with herring with the spatio-temporal changes in herring populations, we identified potential social-ecological tipping points in the system. Specifically, we identified thresholds of herring abundance and distribution that exist for meeting cultural objectives. Such cultural objectives include, for example, resource access, knowledge sharing, identity, cultural food and feasting practices, conservation ethics, spiritual importance, and community social relationships. When there is enough herring and roe on kelp to harvest in the right places at the right time, community members can take part in harvesting and share knowledge across generations about where and how to harvest, process and use herring, and maintain these cultural values. Herring roe on kelp, known locally as k'aaw, is an important food in the seasonal round and contributes to community well-being, health and food sharing. In addition to these harvest values, herring are important to Haida as a way to connect with the ocean and other animals linked to herring.

Eliciting definitions of “sustainability” to inform ecosystem-based management of herring fisheries that balances environmental and cultural values and uses

A guiding principle of the Gwaii Haanas Interim Management Plan (GHIMP 2010) is to “balance protection and ecologically sustainable use,” a goal that extends to all of the land and seascapes of the Haida Gwaii archipelago19. Furthermore, the GHIMP stipulates that management actions in Haida Gwaii must respect a range of environmental, social, economic and cultural values. However, there remains some ambiguity with respect to how ecological goals for sustainability intersect with social, cultural, and economic goals. To explore how people define sustainability in the context of their wellbeing and their relationship to the marine environment, we used mixed participatory social science research methods. Starting with categories of sustainability and the herring fishery generated from existing documents, we implemented semi-structured interviews with local people. We held workshops where residents of Haida Gwaii were asked to sort a series of statements about sustainability and the marine environment using a “Q-methodology.” This provided an understanding of the factors that influence perceptions of sustainability in the herring fishery and ecosystem management.

A guiding principle of the Gwaii Haanas Interim Management Plan (GHIMP 2010) is to “balance protection and ecologically sustainable use,” a goal that extends to all of the land and seascapes of the Haida Gwaii archipelago19. Furthermore, the GHIMP stipulates that management actions in Haida Gwaii must respect a range of environmental, social, economic and cultural values. However, there remains some ambiguity with respect to how ecological goals for sustainability intersect with social, cultural, and economic goals. To explore how people define sustainability in the context of their wellbeing and their relationship to the marine environment, we used mixed participatory social science research methods. Starting with categories of sustainability and the herring fishery generated from existing documents, we implemented semi-structured interviews with local people. We held workshops where residents of Haida Gwaii were asked to sort a series of statements about sustainability and the marine environment using a “Q-methodology.” This provided an understanding of the factors that influence perceptions of sustainability in the herring fishery and ecosystem management.

Residents of Haida Gwaii, both Haida and non-Indigenous, offered to us several ways that the sustainability of their households and communities are linked to the status of the marine environment. Fisheries, such as salmon and herring, are among the most commonly identified ways that local people depend on marine ecosystems, but people also noted numerous additional amenities that relate more broadly to their quality of life. That is, the natural spaces of the Haida Gwaii archipelago do more than simply provide food and economic benefits for local residents. Local people shared with us a deep psychological and cultural connection to the place; parents describe the benefits of bringing up their children there, and youth talk about the archipelago as a place of possibility. Many non-Indigenous families, for example, talk about how both the abundant natural resources and the overall quality of life provided by the rich local environment, offset for them the challenges of remoteness posed by living on the Archipelago.

Residents of Haida Gwaii, both Haida and non-Indigenous, offered to us several ways that the sustainability of their households and communities are linked to the status of the marine environment. Fisheries, such as salmon and herring, are among the most commonly identified ways that local people depend on marine ecosystems, but people also noted numerous additional amenities that relate more broadly to their quality of life. That is, the natural spaces of the Haida Gwaii archipelago do more than simply provide food and economic benefits for local residents. Local people shared with us a deep psychological and cultural connection to the place; parents describe the benefits of bringing up their children there, and youth talk about the archipelago as a place of possibility. Many non-Indigenous families, for example, talk about how both the abundant natural resources and the overall quality of life provided by the rich local environment, offset for them the challenges of remoteness posed by living on the Archipelago.

Four themes emerged from the research around how to define sustainability:

- Local control, by which people mean that local communities are best able to achieve the sustainable management of local resources. As such, locals believe that long-term sustainability of Haida Gwaii communities depends on whether decisions about environmental resources can be made locally.

- Local food access, by which people are speaking to the imperative that local fish resources be allocated to local users before export markets.

- Livelihood security, with a focus on how local people can pursue meaningful and fulfilling life pursuits, and whether youth see a future for them on the Archipelago. With respect to environmental issues, this relates to continued opportunities for locals to pursue environment-related careers.

- Community security, focusing not just on community-level food security but also whether the environment can be a context to bring together the diverse populace of the Archipelago, and develop a shared sense of community. Widespread community opposition to oil and gas development is an example of an environmental issue that has brought Haida and non-Indigenous people together.

Working specifically with local youth (workshop participants age 18-30), the research team identified three additional criteria for the sustainability of uses of the Haida Gwaii marine environment:

- When local people recognize the importance of their role in local ecosystems

- When people show respect to local ecosystems, through traditional rituals as well as new, scientific rituals such as monitoring

- When people see Haida Gwaii’s land, sea, and people as interconnected

Finally, Haida participants in the youth workshops also identified a personal tipping point regarding their feelings about living in Haida Gwaii. Several discussed how the resurgence of Haida identity and rights in recent years, embodied by the creation of Gwaii Haanas and Haida assertion of sovereignty over local timber operations, has increased youth empowerment and pride. Some participants in the workshop talked about how going into Gwaii Haanas is a healing act, both personally and culturally.